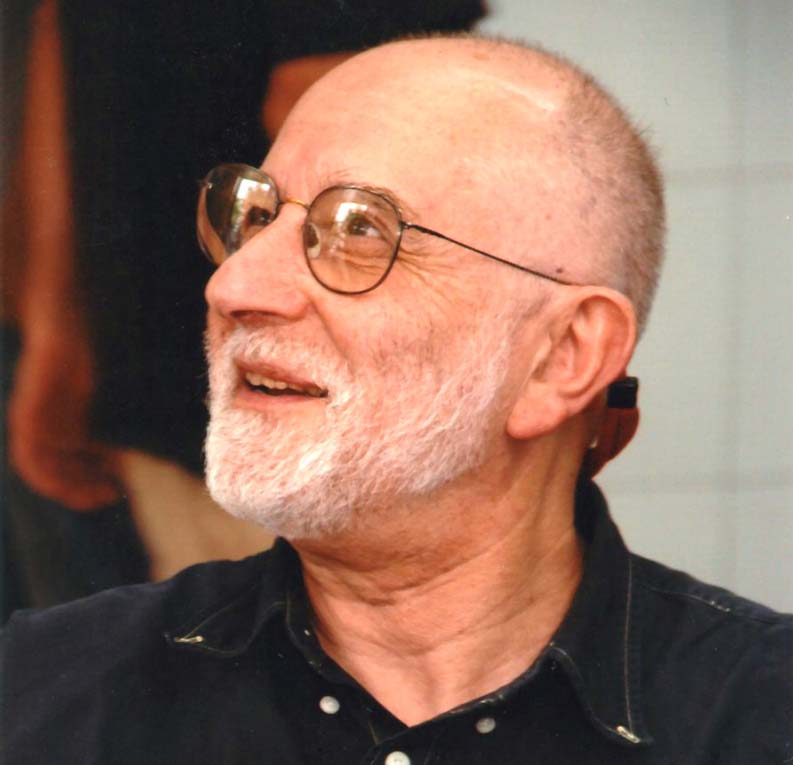

An Interview with Professor Sir Michael Berry (text)

Sir Michael Victor Berry is a professor of physics at the University of Bristol. He specializes in semi-classical optics (asymptotic physics and quantum chaos) applied to wave phenomena in quantum mechanics, and other areas such as optics. He is famous for the Berry phase, which is a geometric phase observed in quantum mechanics and optics.

Sir Michael Victor Berry is a professor of physics at the University of Bristol. He specializes in semi-classical optics (asymptotic physics and quantum chaos) applied to wave phenomena in quantum mechanics, and other areas such as optics. He is famous for the Berry phase, which is a geometric phase observed in quantum mechanics and optics.

Sir Berry is recipient of numerous prestigious awards including the Wolf Prize, the Dirac Medal and Prize, and the Ig Nobel Prize for physics.

Sir Berry visited CMI during the first week of April 2015, wherein we had the chance to ask him some questions regarding his life, work and interests.The video of the interview can be found here.

What follows is the text of the interview.

Q : Do you have a role model, somebody who inspired you to pursue physics?

A : It’s an interesting question because I had an unusual scientific trajectory in the sense that I didn’t work with a senior person ever in my life, except once. In the 1970’s I wrote a paper with one of senior colleague together. But when I was a graduate student I didn’t write anything with my supervisor. He was very helpful to me but we never wrote down anything together. So, I am sort of self-constructed.

However, there are a few people that I enormously admire. Of course there are the usual people we all admire like Einstein, Newton, Dirac and so on. Dirac comes from my city Bristol. I often walk past the house where he was born. But among people who have specifically inspired me there is an applied mathematician called Joseph Keller, who is now 90 something and still very active. He is in Stanford. I admire him. I have admired him from many decades but I only met him some decades after I encountered his work. And then there is some Irish physicist G.C. Stokes. He influenced me and in fact this dates from a visit to India, many years ago, 1988, the centenary celebration of C.V. Raman, a name you know ofcourse. And a number of people didn’t arrive at this meeting in Bangalore and I was asked to give more lectures. So I gave a number of lectures on different aspects of my research and then suddenly I realised that every single lecture I was speaking about was based on some idea that went back to Stokes. So I found out much about him. I admire him very much. Though his style was very different from mine, he’s somebody I admire but I wouldn’t call him role model. And then J.L. Synge, an Irish relativist who had a wonderful clarity in his writings. I met him when I was a graduate student indeed. Almost by chance he influenced the whole direction of my future research. In my own department there was a tradition of geometrical thinking. No one is mathematical as me but still geometrical and pictorial thinking which I absorbed after a few years in Bristol and that has affected me and some of those people in particular the way in which some of them have avoided bureaucracy in their lives in organizing things. I have also avoided have been as closest you could think to role models but no one is exactly a role model. I am sort of largely self-constructed but I have influenced in a number of ways.

Q : What motivated you to take an interest in physics?

A : As a child I was fascinated by astronomy. I think great many physicists and mathematician’s started out by being fascinated by astronomy as children. It’s interesting. You can speculate why. It isn’t really clear to me. We live in a world where children as me listen to the news or they hear it, they see the newspapers. There’s a lot of trouble in the world. It’s somehow comforting to look at these realms very far from all of our troubles. Of course, I now know that the universe is an extremely violent place and our earth is a “fairly peaceful little enclave”. But still that’s just a guess why astronomy is so attractive. A world that’s beautiful and away from our human troubles. But anyway I went to university and realised

that, astronomy is based on physics and physics has beautiful ideas in it which then superseded the astronomy. I still like astronomy as a member of the public but I am not… this isn’t the center of my research.

Q : Could you describe a typical working day of yours?

A : Many years ago I gave a series of lectures in Chicago and my host was a very distinguished statistical physicist Leo Kadanoff. He is a very famous physicist. After the lectures I gave on subjects very different from his, he said, “It is very interesting for our students to hear you, to hear somebody who has a well-articulated research plan.” I said to him, “Leo you are mistaken.” Often when I go to work in the morning I have no idea what I going to think about that day. So it might appear to you as though I have a work plan but often I don’t. However, if I am intensely involved in a problem this occupies me continuously. So wherever I am, when I am at home, when I am half asleep or whether I am at work by my office I am thinking all the time about this problem and technicalities, usually mistaken thoughts. I mean most physics you do is wrong but one makes some progress and so I don’t really have a plan as such. I actually don’t. I am organised person, things like limited work I have to do, the bureaucratic kind like booking air tickets. I am flying different parts every week to another country, booking air tickets and arranging hotels all I do very efficiently. But it is not what I would call my working day. I do that to leave myself space. I try to reply almost instantly to emails and just to get them out of the way some people leave them for several weeks but I can’t do that because they worry me all the time. I think I should be

replying and I do it.Then I get on to thinking about physics or mathematics or whatever.

Q : What do you do in your free time?

A : Cook. I like walking and I occasionally go to cinema. I read a great deal. All kinds of books like philosophy, novels and history. Now I am reading a book about Newton’s studies of the chronology of events in human civilization based on the Bible. He spent more time in his life on this, which we now think is a kind of nonsense actually than he did on physics for which we admire him. I am also reading a novel that my son gave me. So, I read a lot and I like cooking. That’s what I do. I like to walk also. I don’t get much chance but there’s a lot of nice countryside where I live. When I visit places not so hot as India. I like to walk.

Q : So, like the Berry phase, is there also a Berry recipe?

A : No. Not at all. I mean I cook food from all countries. I love to make Indian food actually and also Brazilian food. There are many different things. But my favorite activity is to come home, my wife and I don’t quarrel much on who is going to do the cooking. We both like it. But almost my favourite is to go home, look inside the fridge, see what is there and make something which will never be repeated. So this is opposite of having a recipe. Well I do occasionally like to follow recipes but nothing in particular.

Q : What movies do you like?

A : I don’t like musicals. I have recently seen the movie about Stephen Hawking. I saw it while coming here on a plane. And there is another about Alan Turing. I liked both of them. These are two recent movies that I have seen.

Q : What is your favourite genre of music?

A : Jazz of all kinds.

Q : Any favourite artists?

A : Oh yes. I mean there are different musicians who reach deep into the heart in different ways. I dream of doing a piece of theoretical physics which has the same immediacy and beauty as one note from Louis Amrstrong’s trumpet. There is a saxophone player called Sonny Rollins who’s been playing for almost 70 years and I have 30 or 40 of his CD’s. This music touches very deep into me. The quality of the sound he makes is particular approach to melodic improvisation. And to mention the famous people like Duke Ellington and I like the great people related to this realm of music. Melody

Q : What about the younger artists, who do covers of great songs? Do you listen to them? How do they fare compared to the greats of the earlier times?

A : Not that much but there are some very good musicians who aren’t so old. I occasionally hear them. I don’t know the latest of them but of course now it’s possible with the improvements of technique that people make for people to copy and sound like these musicians from older times. It is fun to listen to them but of course it is not the original. Even if you do it perfectly, it is not the same as creating. You know there are people who are much more mathematically proficient then Schrodinger when he wrote his wave equation. But he is a great man unlike the others. It’s only because he created the thing.

Q : What about improvisations and reinterpretations?

A : Oh yes and no. That’s a standard procedure in jazz. It’s that, there are certain melodies which there are like ‘Summer-time’ and are sung by a variety of musicians, each of whom has his own way of interpreting and I love that. I mean those are called standards. I like this. Yes, there is another thing. There is something about jazz which is, I wonder how to write about this in more detail, which is a bit like theoretical physics. The improvisation of a group of jazz musicians, the way they bounce ideas of each other, they exchange, suddenly improvise and then repeat some. It’s like the kind of conversation between theoretical physicists.

Q : And now for a few technical questions… How do you explain Berry’s phase to a layman?

A : When you reverse your car to park into a small space, you sometimes find that you were not very efficient in doing so. Yet you still had some distance left from the curb. It takes a lot of maneuver to get close to the curb while you park. And there is a reason for this, because while driving you have two things to do, drive and steer. And these two activities don’t commute with each other. If they do then you can do all the steering in your garage before you left home, but you can’t. Now while parking you make a series of periodic maneuvers or cyclic series of changes and after each cycle the car shifts. Now this idea is a geometrical idea, you can change something periodic cyclically to make shifts so it doesn’t come back the same as before. This is a branch of geometry is called parallel transport, and the geometric phase is an application of this idea to the oscillations you get in waves. In a wave something is vibrating all the time, if you slowly change the conditions under which the wave is propagating in such a way that you come back to the same conditions as you started, that’s called a cycle. If you ask what is the state of oscillation of the wave which is called the phase then the answer is not what you thought it was. It is not the sum of the little individual oscillations. There’s the partial essence of geometry. I call it a kind of quantum memory. The ordinary oscillation takes place even if you don’t change anything present there all the time. To answer the question “How long did your trip take?”, after sometime the geometric phase partially answers the question of “where have you been”. So that’s what I would say, using this analogy with car parking.

Q : What are the applications of Berry phase?

A : Well that’s a good question. I am not so interested in that. Actually I am very happy when people say that they are applying it. There is something called adiabatic quantum computing and the dream is that this type of phase might be like the basis of techniques for making a quantum computer which diminishes the liability to external noise. The problem with quantum computing is that it’s a very delicate, coherent thing and while a computation is going on you mustn’t look at the processing. Indeed any influence from outside produces which is called de-coherence, washes out the delicate interference that enables quantum computers to be efficient. The idea that if you base a quantum computer on something geometrical, that’s less vulnerable to the influences from outside than the techniques that people use at present. Well there’s a large activity called adiabatic quantum computing based on geometric phase mostly as theory and there are a few little test experiments. But as you know a quantum computer doesn’t exist yet so it’s only rocked that has a serious usefulness. So there’s that and in optics there are various kinds of optical switches based on polarization that have been proposed and they work. I am not sure how practical they are compared with other switches. There are many applications within science namely condensed matter physics, the whole subject of topological insulators, quantum hole effect and aspects of graphene, the geometric phase is central to all of those. But that’s all within science. I think to answer a question if you mean an application in the lives of people who are not scientists; if you mean that within the realm of science there are many alike.

Q : You recieved the Ig Nobel prize along with Andre Geim for “The Physics of Flying Frogs”. Could you tell us more about the experiment and the Levitron?

A : In 1995 or 1996 I was visiting Zurich with a friend who said there is a very interesting toy shop in Zurich( a scientific toy shop). It has the name “Aha!”. Well, this toy shop in a little street called Spiegelgasse is immediately below the apartment where Lenin lived when he was planning the revolution and it’s just up as street from the cafe where he used to sit. It was then where the cafe owner made the famous statement: “Those guys will never make a revolution. They are only talking.”

Anyways I went to this shop and there was the levitron. The levitron, you know what it is, it is a scientific toy where you have a magnet inside the solid wooden base or plastic and the spinning top, which is magnetised, which you spin and suspends above it. And I was immediately fascinated by this toy and I made them some comments. I was thinking all the time about it, “Oh this looks like the kind of a macroscopic analog of the kind of traps in which scientists hold microscopic particles.” You know “how does it work; how …” , the shop assistant was, I would just say stupid. She said, “Oh we are not interested in these details. We try to understand the universe as a whole.” Idiotic (!). The American expression is ‘airhead’. But still I said, “I’ll buy it.” “Oh you can’t buy it. It’s the only one we have.” Okay. So I couldn’t. But then somebody bought me one and I spent a long time understanding how it worked. Now, ofcourse it was invented. Now, it was invented by people who had planned applications which I read and they did not understand the physics at all. There’s a fundamental theorem which you applied rigorously would have told any physicist that it was impossible to levitate a magnet above another. But there’s a little loophole which I discovered and saw how it works but it is very delicate. There is a tiny tiny region of stability and you have to make sure that the magnetic field balances gravity so they have equilibrium in this narrow region where you have stable equilibrium. It’s a geometrical thing which evolves through the force of the magnetic field, it’s a technical calculation which I was very happy with and I published it and for a time I was giving lectures. This levitron is quite tricky to operate because of its delicacy. Indeed since magnetism of a lump of metal depends on temperature, if you raise high enough you get the Curie temperature and it disappears. The height at which the top is hold at equilibrium depends on temperature and you have to change little weights on the top to make sure that you stay in that stable zone. So that’s quite delicate and most of the time you fail. I became very good at it because if you give lectures then you must make sure that you can achieve it in a lecture theater with people. So I managed to do it. I’ll tell you a funny story. I was in Bangalore and I was invited to give a lecture. My son suggested I should give the title, “Levitation without Meditation”. So I gave this title and my host called me and said “Look, I am a bit worried about your title because it might attract the wrong kind of person. Can you supply an abstract technical enough to repel such people?” Well I did it and on the day of the lecture the email came advertising my lecture, “Levitation without Mediation.” I was so angry that I called them and I said, “Look, you’ve ruined the title. Please send an email with would create otherwise I am not giving the lecture.” Well I gave it. So I was giving this lecture in a few places. It was popular. People liked to hear it. It was a good story. But, one place I went to there was a specialist on magnetism. He said, “Do you know that there’s a guy in The Netherlands who’s levitated a frog.” I was, “No, it sounds like non-sense. You know, it couldn’t be.” He talked about as though it is completely different but then I had looked at what the guy had done. He hadn’t published it. It was on a website. It was the early days of the internet. And then I realised that it is sort of the same because it works because the frog is water, I mean it’s basically water. And water is diamagnetic, diamagnetism is also little circulating electrons which is like a spinning top. The theory is not exactly but almost the same. But he, this guy, I went and met him. He’d done his experiment. He had a huge powerful magnet than other of the magnets on condensed matter physics. And the unique feature of his magnet of 16 tesla, which by the way used 6% of the electricity supply of the town where he was so he was only allowed to use it on non-peak times when people won’t be cooking their dinners and so on. So, the unique feature was that it wasn’t at low temperatures and it wasn’t in a vacuum, it was in air. So he thought he’d try this idea of repelling but he found it very difficult to tune the magnetic field, the position and so on. He did it, empirically. But I gave a theory which precisely to a few millimetres indicated why he had to use the conditions that he had found empirically. So we wrote a paper together. I did the theory and it was his experiment. And then after sometime he called me and said, “I have been invited to accept the Ig Nobel Prize. Should I accept it?” And I wrote him and said, “Look, it’s a kind of fun thing in America. Some people don’t like it. They think they are making fun of science but they’re not, actually. So if you find yourself in Harvard when they have this rather stupid ceremony, I don’t see any reason you shouldn’t accept it.” But he telephoned the guy Marc Abrahams and said that I would accept it given that you give it to Berry as well because we did this together, he did the theory. So that’s how I came to be involved but I didn’t go to the ceremony as I had a conference commitment somewhere else at that time. But anyways it’s rather kind of silly thing. So that’s the story of the frog. It’s essentially the same as the levitron, not exactly and I did the theory and Andre Geim, who later went on to get the real Nobel prize for graphene, different thing, he did the experiment.

Q : A couple of philosophical questions… Do you believe in God?

A : No, not really. You know, let me tell, my brother is religious. I am Jewish. I am not religious at all. My brother is a rabi. He is a minister of religion he thinks I am religious but simply not in the usual way Because he thinks what I do amounts to a kind of worship of the universe in its deep structure. Well he can make that definition if he wants and we are very good friends although he knows that I would be never be converted. I am a lost cause to him. But what I don’t agree with is any of the organised worship and the rituals and the sacred books. But I want to say something, It’s very important to say this. There are people, my brother being one of them, with whom I deeply disagree on these kinds of matters. However, I also am aware that there are many people with whom I disagree, whom I respect enormously as human beings, I really do and a number of them are among my friends, not just my brother. On the other hand there are people with whom I agree and whom I dislike so much that I wish I didn’t agree with them. So it’s much more complicated. It’s not a simple thing at all. But if you would ask me the straight forward question in the usual way if I believe in one of the many religions, the answer is no. Now let me tell you. We have in England a famous atheist called Richard Dawkins and he was talking to a priest and the priest said, “Do you believe in God?” And he said, “No and actually nor do you.” And the priest said, “What do you mean? Ofcourse I do.” So he said that “Do you believe in Ra, the sun God?” “No.” “Do you believe in Thor?” “No.” “Do you believe in Vishnu?” “No.” “There are about 6000 different gods that believe in and you believe in only one of them.” So you are almost the same as me. So just a fun response I know that in Hinduism you have many Gods, that’s a very healthy thing. Hinduism seems to be, apart from some nasty politics, seems a very tolerant religion. I understand that and sympathise with that very much.

Q : There is even a branch of Hinduism that’s completely atheistic.

A : Yes, I know. There are many different branches within. Yes.

Q : In your opinion does good research come out a specific purpose or end in mind or do the ideas come out organically?

A : Both. You know, I was speaking in this room this morning and a very important concept is that chance favours the prepared mind. So sometime it can seem that some chanced remark that somebody makes, you know the geometric phase, I discovered it after somebody during a lecture asked a particular question and not before that. I thought about this question and I realised there was something deep there and it took several weeks then I found the phase. I might have found the phase otherwise. I had all the ingredients in my mind. It didn’t happen that way, it happened almost by chance, but as I say, the prepared mind. On the other hand, sometimes you can really say, “I want to work this damn thing out.” And you work and you work and you work and then you do or you don’t but if you do that’s the organized problem solving and I do both, so do happen.

Q : Given the fact that most research today focused on “fashionable” topics, how do you think academia can help students to pursue topics they are really curious about, rather than these “fashionable” topics?

A : It’s a good question. I think that certain fashionable topics are very interesting and worth studying. Topological insulators, graphene, string theory, you know all those. My own taste is not to work on those things. I never advise other people to do it or not to do it. But as I again said this morning, I am not a very competitive person. I wouldn’t like to everyday see on the archive and see what people publish. It’s good, physics is very important. I also said I have to repeat it. I was in Korea last year being interviewed by a newspaper and the first question they asked was, “When will there be the first Nobel prize in physics for a Korean scientist?” And I said, “Never if all you do is work on fashionable subjects because although it’s good science, it’s developing ideas which originated elsewhere and they’ll get the prizes if there are any.” So that’s my comment. I don’t work on quantum information but I think it’s a wonderful subject and when students say, who are not my student, but they I always say quantum information, the physics of entanglement is something where we know really rather little. Even the Hilbert space of three particles has not been properly explored. It has a fantastically rich subject possibilities which will change civilization in the way that Maxwell’s equations changed civilization and ordinary quantum mechanics with the transistor and the LASER changed civilization. Leon Lederman, Nobel Prize winning experimental high energy physicist estimated that about a third of the gross national product of the industrialised world is a direct consequence of quantum mechanics. Well that’s the quantum mechanics without the modern entanglement and this so this will have a, you can’t predict how it will happen. At the moment there is something a bit dissapointing which I tell sometimes to my colleagues in quantum information we’ve had 25 years or 30 years of quantum information, wonderful deeper and deeper understanding, but many still unsolved problems. But the only practical application is to cryptography. Now it’s worthwhile. I don’t want people to be able to get into my bank account but keeping of secrets is not really a positive human thing. I would have hoped that there would be some more positive application. There will be, I am sure there will be. It’ll happen. But so far this keeping of secrets is a kind of miserable thing. You know, you have to keep some military secrets or like I said your bank account but most things, you know, I was reading a newspaper article by a famous British writer called Howard Jacobson and the title was something like the Curse of passwords. And he said, “I had received an email inviting me to a literary festival.” And they said, “We’d be very honoured to have you speak at our festival. To discover the time and place where we’d like you to speak please login to our website, create an account with a password and then you’ll find a message. You’ll see the programme.” So he wrote them why don’t you just tell me that you’d like me to speak at this time and this place? And they wrote, “It’s too complicated of too many speakers.” So he says, “I never replied, I am not going to such a place.” Well very often if I am sent a paper to a journal I am asked to refer a paper. They say, “Oh you got to login to our website.” And I say to them, “Ofcourse when you refer a paper you don’t publicize the report. And you are discrete, it’s not like a national emergency. It’s not so important if somebody discovers what you write so I am not going to do. So just send me the paper.” So, I don’t think this vast technology of keeping secrets and passwords in the quantum version of it is so important, I mean it’s not a positive human thing which I would like to see. I would like to see some analog of application of quantum information which is positive like the compact disk player or the GPS which changed people’s lives in a good way. You know some of the medical applications like PET scan (positron emission tomography) based on the annihilation of the positrons emission in your brain. This quantum mechanics and relativity really helping people although but so far not.

Q : The thoughts and ideas of Einstein, in his time, were a fundamental shift from the ‘conventional’ knowledge. Is there a chance that there will be such a shift in our time?

A : Oh it’s a very good question. I wouldn’t say that Einstein changed the conventional way of thinking. He changed the previous way of thinking. Of course it’s never been true that members of the public understand Newtonian mechanics, certainly not of rotating bodies. That’s still very complicated. It’s a subtle thing. But he did that and the quantum mechanics people as well did that by creating a theory based on experiments which involved radically different concepts. Now the problem at the moment is that quantum mechanics is too damn good. There are no experiments that contradict it. One day there will be. I’m sure, it’s not the last word. And then in order to accommodate new discoveries there will be, it will take some time, some theoretical framework which is radically different, from quantum mechanics will emerge in the same way that classical physics emerges from quantum in a way that’s not straightforward but it does when you can neglect Planck’s constant. But you can’t predict how it’ll happen. See quantum mechanics was invented in response to experimental observations on the spectra of atoms and molecules which just couldn’t be explained in the old classical way. But we don’t have that at the moment, we don’t have such experiments. So people do grope around and people try to find theories underlying quantum mechanics but none of them is very plausible because there’s no evidence for it. Look, we are a very young species. You know, we have only been around for a few thousand years as a civilization, a few hundred years doing the kind of science we do now. The difference from earlier ideas being the science that we do now is communal. We talk to each other and even thought we are proud of our individual achievements we learn from each other. So it’s more like a group mind which is more powerful than one person and that’s why science advances so fast but still we are living we are a limited species, you know, there could very well be aspects of the universe too subtle for us at our present stage of evolution ever to grasp. So whether we can go seriously beyond quantum mechanics, I don’t know. It depends only on observational experiment. I really can’t predict. As someone says, “You can predict. Prediction’s very easy except about the future.” If there is an alternative theory that predicts a particular thing different from quantum mechanics then found then great. But there’s nothing so far.

Q : What should be the primary motivation for doing science?

A : It’s upto people who do it. There are different motivations, as you’d know. There are many reasons, some people do science to become famous and meet women or men. Sometimes people do it to earn lot of money. Most scientists don’t do that. They do it because of the thrill of discovery is so wonderful that everything else is insignificant. So most people don’t do it for the money. But I can’t say what you should do. I mean there could plenty of scientists who do it for money and fame who do very good science. People’s private motives can vary a lot .But it’s as Feynman said, “It’s the pleasure of finding things out” to quote him. And by the way, just to say, I am still astonished that for my whole career and now that I have officially retired, people actually paid me money (a salary,) to have such fun. I am very grateful to be in a society civilized enough to be able to do that.

Q : How do popular science TV programmes contribute in the making of young scientists?

A : It’s actually, I think, very important. There’s a certain improvement in the quality of these programmes right now. In particular in Britain we have a guy called Brian Cox and he isn’t like Michio Kaku who stresses the frontiers of physics in the possible futuristic notions. He talks about the quite mundane things that classical physics will, but in a way that is very charismatic and powerful and it’s probably him who has had an influence in enormously increasing the number of students doing physics in the UK. There was a time, like in the most places in the world, physics wasn’t the most popular subject. It went down to doing media studies and this and that. Well, that’s different now. Our department is bursting at the scenes. We have more good applicants than we can accept. You know this is all happening with us right now. I suspect that a large part of that is due to these TV programmes which presents science in a way much better than they used to be before. They used to be purely sensational and kind of personalistic and they are much better now.

Q : You have visited India before. Could you narrate some interesting experiences from your visit?

A : I had lots of interesting experiences in India. The most beautiful day of tourism I have ever spent many years ago, on the backwaters in Kerala, on the boat from Alleppey to Kottayam. There were so many, I mean, I am visting many countries. As I said, I am travelling almost every week to a different country. I was in Brazil last week, I came back and spent one day in Germany and now I am here, next week I’ll be in the USA, the week after that I’ll be in Israel. Every country has its interesting attractions. India is particularly rich. I love the food and, you know, people I meet I enjoy. I haven’t had any real contact with the bad aspects which of course there are as in every country though I don’t want to single out a particular experience. I think they’re, in their own places, wonderful. I want to see the snake park here in Madras because many years ago I wanted to see if snakes really move in the way that de Gennes got his Nobel prize for polymers which used to move parallel to themselves. It’s a non-holonomic constraint in a one dimensional field theory. But I did visit the snake park many decades ago and so they do this. Now I have a snake at home. My son had a pet snake which somehow after 20 years the thing won’t die. It started like this (short), now it’s like that (long). And he’s gone away. His girlfriend won’t allow him to have it in their place. So now I see it but still I remember that snake is a wonderful place. I would probably either to there or the crocodile and snake park close by. You know, but these are just little things. I like just the streets, look at the streets in India. India is a fractal country. Every street is a kind of the microcosm of the whole. You know, you see everything there. You know, people buying and selling all kinds of things, cows across the streets, holy men walking up the street in front of the lorries and trucks. I love it, and then there’s noise. I was in Kolkata once, I had to call my secretary in the street and I said, “Before we talk, listen to Kolkata,” held the phone up. She said, “Sounds very noisy.” I said, “Yes, it is.”

Q : What places are you going to visit during this trip?

A : I want to visit this crocodile park which is close by to here, but then there are some temples in the place called Kanchipuram that I might visit although as somebody says that they don’t allow foreigners any more in there but I will see the place from outside. This is an unpleasant development by the way. I know there’s a lot of discussion about it. So, I might go there. Also just for the fun of being driven out, I’ll rent a car and I’d drive through the countryside in India, seeing little villages, stopping somewhere and having a lunch and somewhere in some little place with banana leaves, and I’d like this. So that’s what I’ll probably do here. There’s also a government museum which I am told that it has beautiful things. I am told that like the government museum in Kolkata, it’s in a disgraceful state of neglect and disrepair. Nevertheless it has wonderful things in it. So I’d would probably see that too. That’s enough. The weekend would be gone by then.

Q : But mainly you’ll be around Chennai only.

A : Ya. No, no, I don’t have time to visit other places, no. Sometimes I do. I’ve visited many different parts of India over the years. But this time not, I am going home on Monday morning.

Q : So what message do you have for students of India and across the world who are watching this?

A : Have fun!

Q : On that note we end this up. Thank you very much.

A : Thank you. It’s my pleasure.